Pathways and Paws(es) evolves out of a single design concept where we wanted to create place-based community networks for dog walkers (and others).

The over-arching research methodology is essentially a kind of ‘grounded theory’ approach meets a ‘practice-based’ approach.

This has resulted in three interconnected / inter-dependent project threads:

- The community project

- The data collection project

- The visualisation project

The community project

The community project is inspired by personal experiences of connection through the act of walking the companion animal in-place. A guiding framework is the contemporary interest in slow cities and movements towards designing urban environments which facilitate grass roots place-making and emphasise quality of life and emergent diversity.

A key concept in the slow cities movement is resistance to homogenisation and top-down cookie-cutter design. This is reflected in the Pathways and Paws(es) community project design which proposes using smart technologies (smart phones) in-place to create networks of trusted walkers.

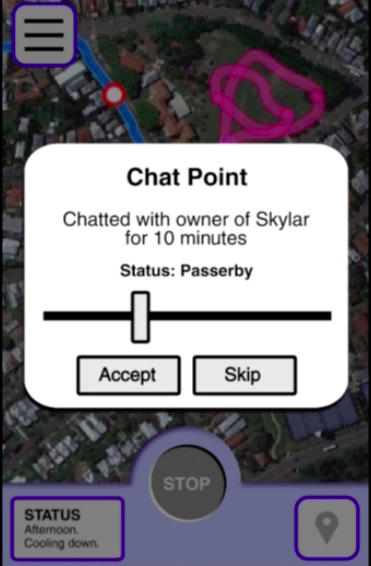

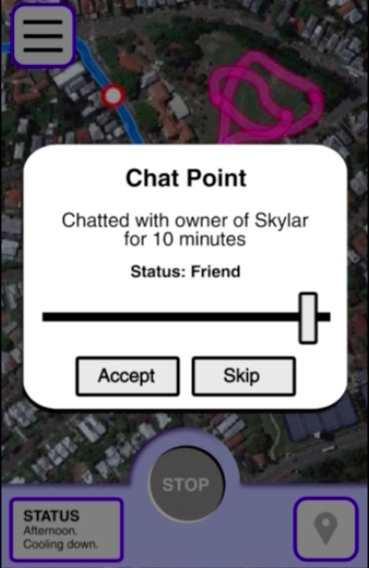

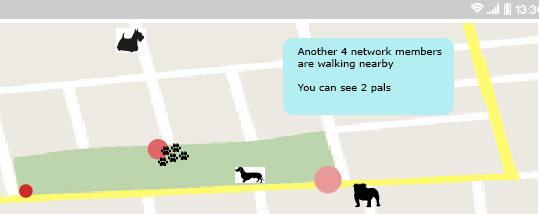

This design concept is distinguished from the multitudinous facebook and meet-up groups and sharing apps which aim to put people in touch via the placeless-ness of the virtual (top-down, homogenised) because it depends on face-to-face meetings as a means to create trusted network contacts. Or rather, nose to nose meetings (or even ‘nose to bum’ meetings) because the connections are created via dog to dog interaction through Bluetooth UIDs and allocated the dog’s name as an identifier.

This type of in-place face to face network is not intended to replace or social media networks. Instead it merely enhances the serendipitous nature of the dog walking community where we typically walk our companion animals at fairly regular times of day and often regular routes or pathways. We tend to meet others in the community whose routines coincide with ours and we also tend to co-perform with our companion animals in the sense that we will stop and talk to walkers when our dogs have a friendly exchange.

Does your dog enjoy playing with some other dogs? Is there a friend in the park? Do you fancy someone to walk with, perhaps explore and find new pathways together? And even, is your mobility compromised and could your friend bring your dog along on their walk?

See design scenarios

Community project research in progress

Participant research - asks questions about dog walker's in-place community network building in order to interrogate insights in more detail with a view to designing the community aspects of the PhoneApp.

Design research - implementation of low fidelity prototypes for user testing

The data collection project

The data collection project evolves out of the initial community project. This aspect of Pathways and Paws(es) is focused by insights about co-performance in the Community project thread and investigates the co-performance of walker and companion animal as collaborative place-makers in urban environments.

Place, as the humanist geographer, Yi-Fu Tuan, observes, emerges out of meaning making and experience. A ‘somewhere’ becomes a place when it is layered with experience and stories. Place-making is a lived, dynamic conversation with the landscapes we inhabit. From the personal (this is the park where I met my friend) to the wider social story (this is where Hemingway wrote The old man and the sea), place is created through experiences.

When we walk with a companion animal, there are two place-makers acting in co-performance: the walker and the animal partaking in the walk. Each collaborative pair is distinct – dogs having as much variety of personality as people – but both (or sometimes all) members of the co-performing partnership are place-making. For the human walker this may be expressed through choices made about particular routes (up the steep hill or take the longer, flat way around), for the dog it might expressed in selection of a favorite area to do daily business (my dog has a selection of sites for example). We both engage in place-based meaning and recognition: I might pass a house and recall the time I lived there, my dog will sit and cry when we pass the home of a known play mate, reacting to sensory information as she has never actually played with the dog outside of the park.

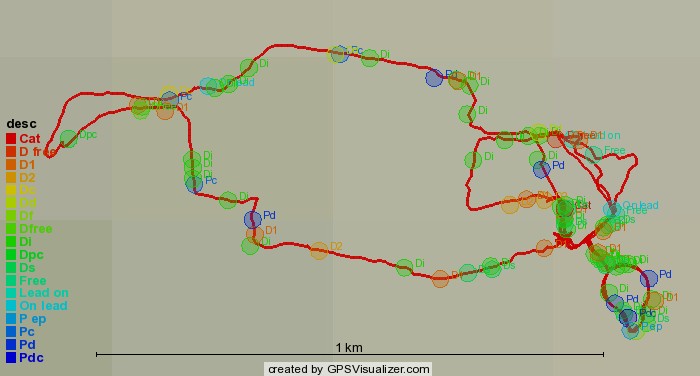

This thread of the Pathways and Paws(es) project aims to collect data that can then be interrogated for insights, hopefully revealing more about the co-performed place-making.

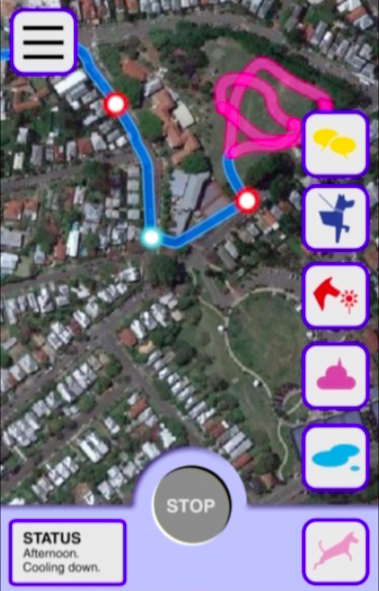

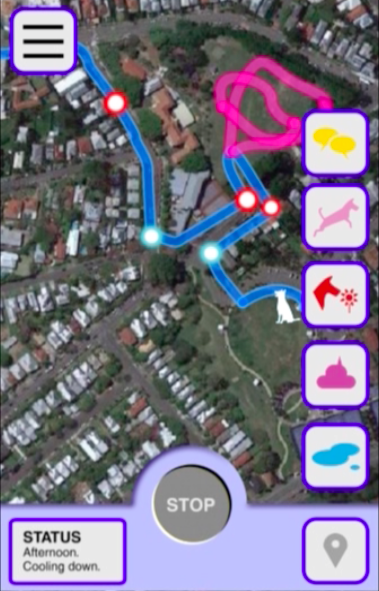

A simple way to collect the data is to use the same app that we have been working on in the Community aspect of the project and add a number of ‘quick waypoint tag’ options specific to the dog walk as a co-performed experience. So, in addition to the ‘add chat’ and ‘add friend’ option, the design also offers ‘off leash’, ‘agentic investigation’ and daily business.

Data collection project in progress

Design research - Data collection pilots have used a COTS app but it is inadequate (or at least awkward) as a means of collecting the variety of different data points. The design work focuses on easy data waypoints collection via a specifically designed smart phone app (PhoneApp) and the design and construction of a multiple tag data input logger (Hardware).

Participant research - testing and developing the waypoint tags in the field with different walkers and locations.

Data visualisation project

There is something tantalising about envisioning geography as place from an animal’s perspective. Given that geography and mapping of landscapes is, in effect, the re-making of place as measured (contained, revealed, sometimes claimed) space, giving voice to those with who we share place is an extraordinary opportunity.

Taking the nonhuman seriously needs to be more than a matter of recognition of the ways in which animals affect the lives of human beings … it requires the very cry of the nonhuman to be heard.

(Johnson, 2008, p. 636)