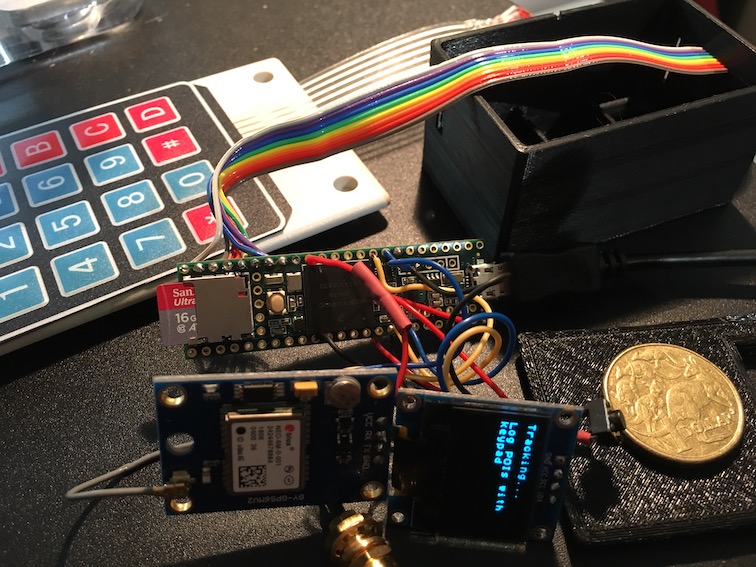

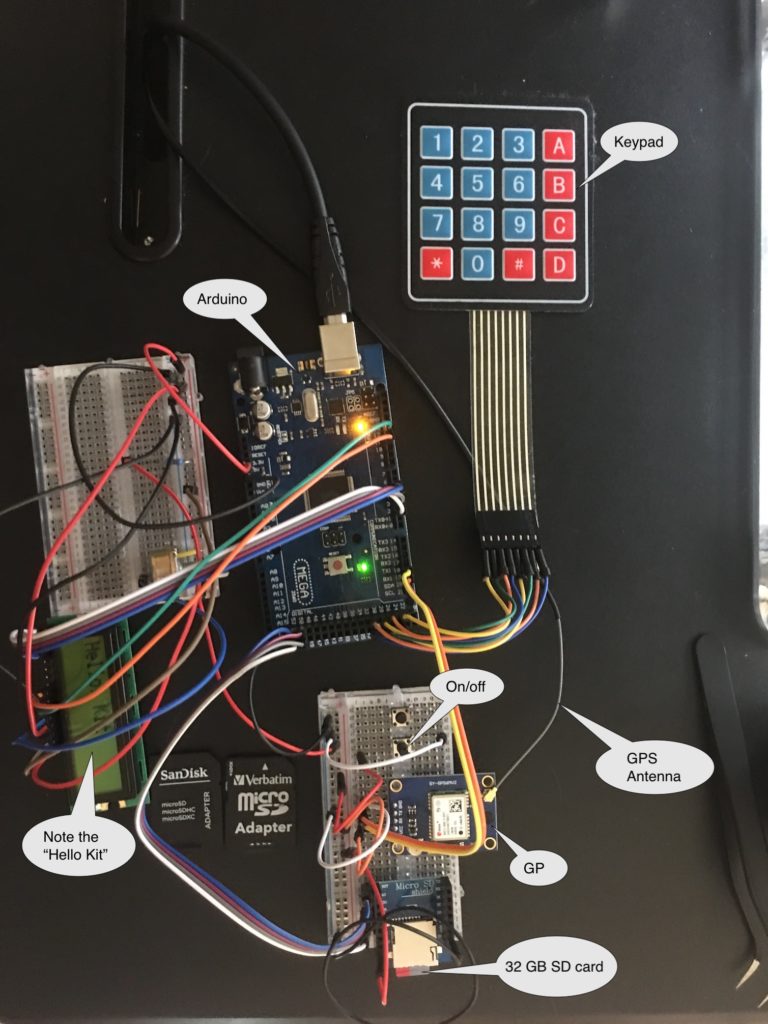

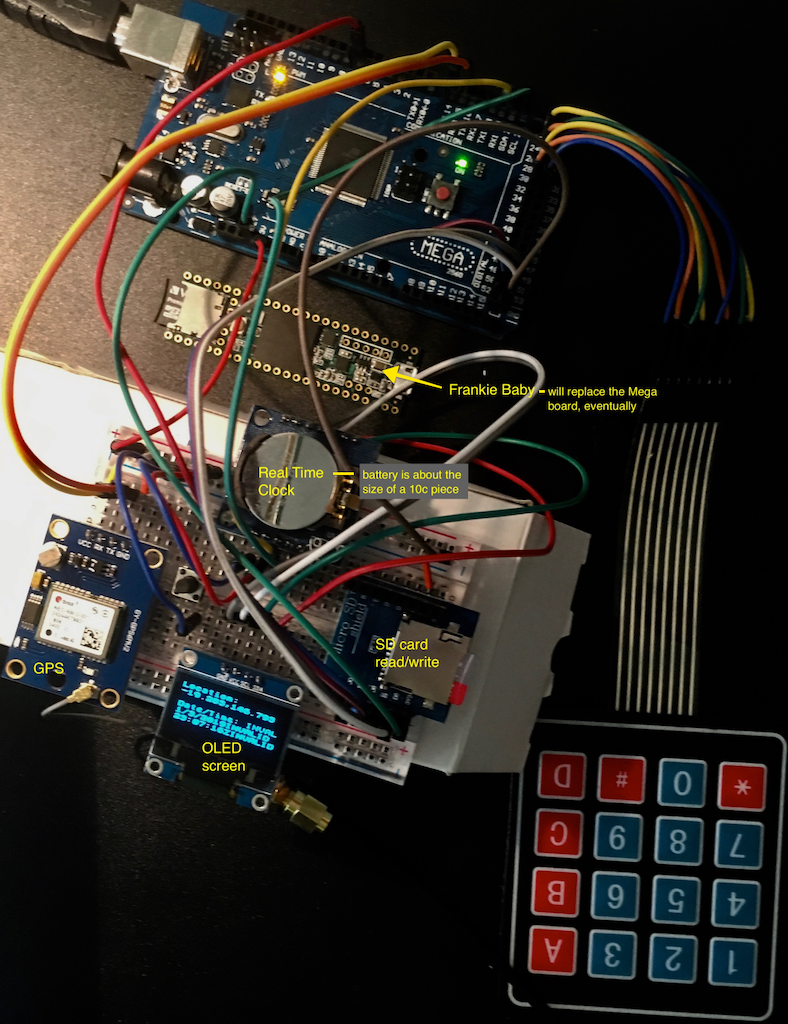

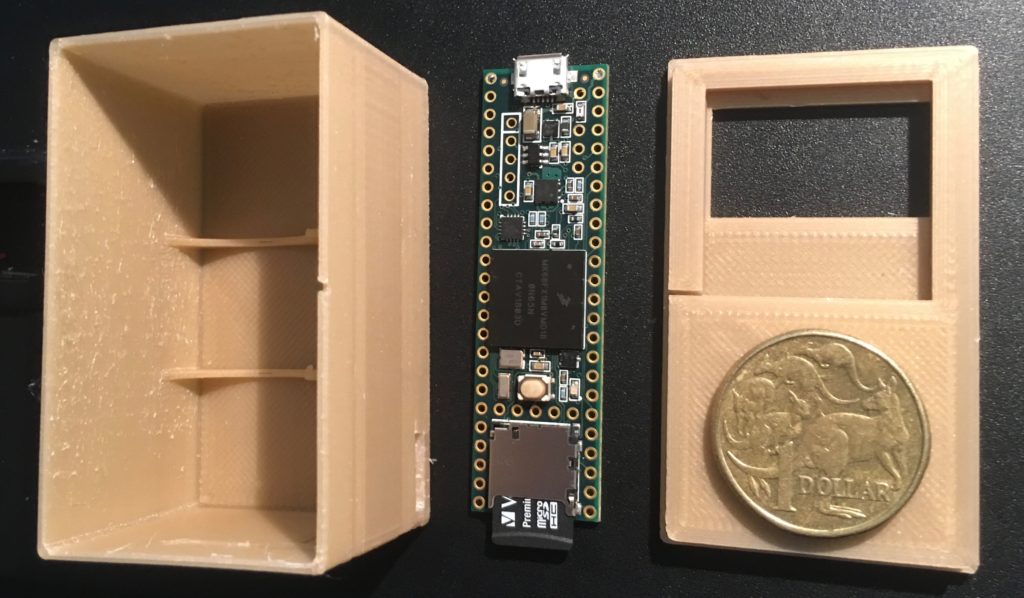

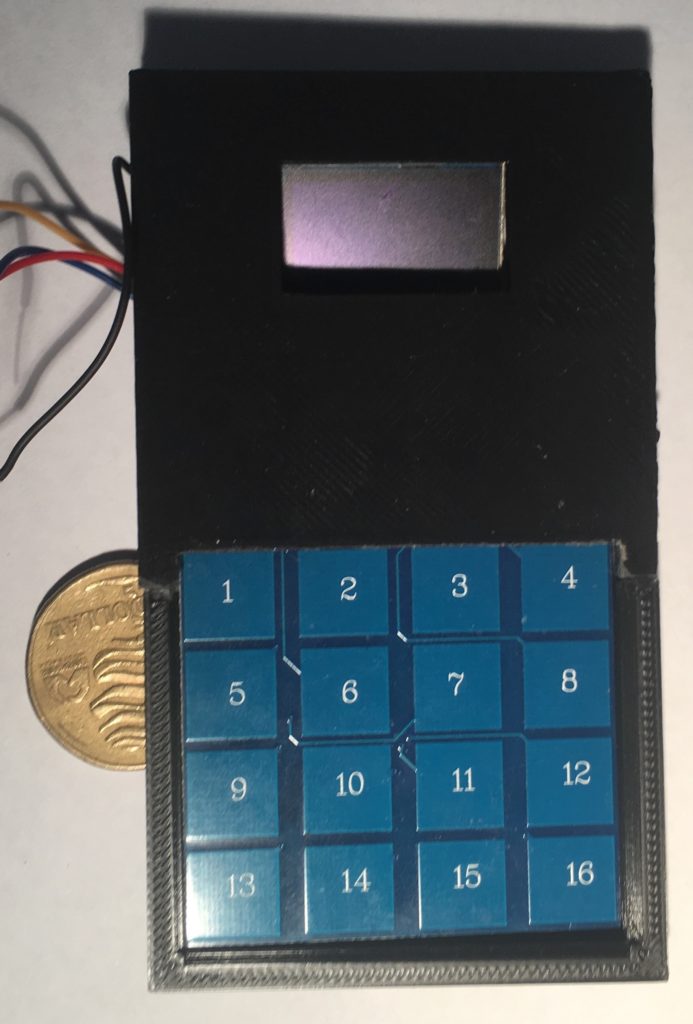

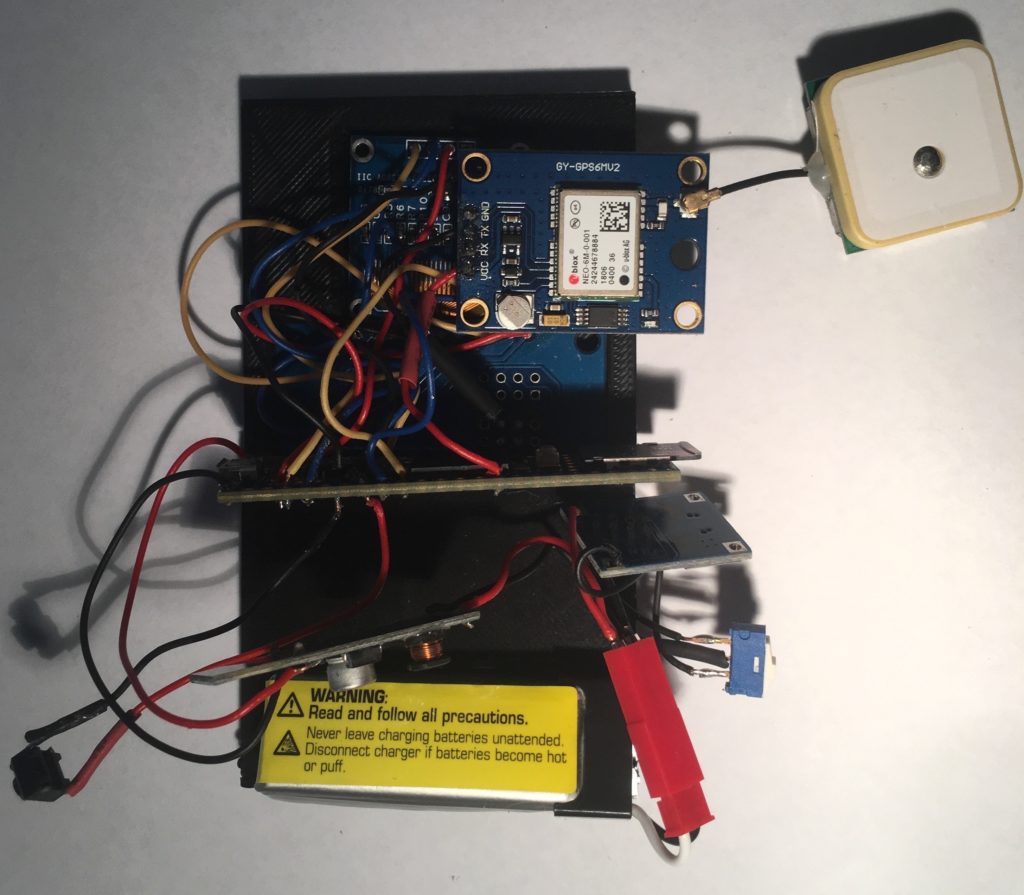

Finally, Frankie now has a 3D-printed lid. Sounds mundane, but this was in many ways the tricky part. It’s in two parts – one holding the keypad, sans suitable labels, the other covering the keypad electronics and holding the OLED screen.

Next, Ill be making the box which the lid fits on to.